11 Dec 2024

Tired Earth

By The Editorial Board

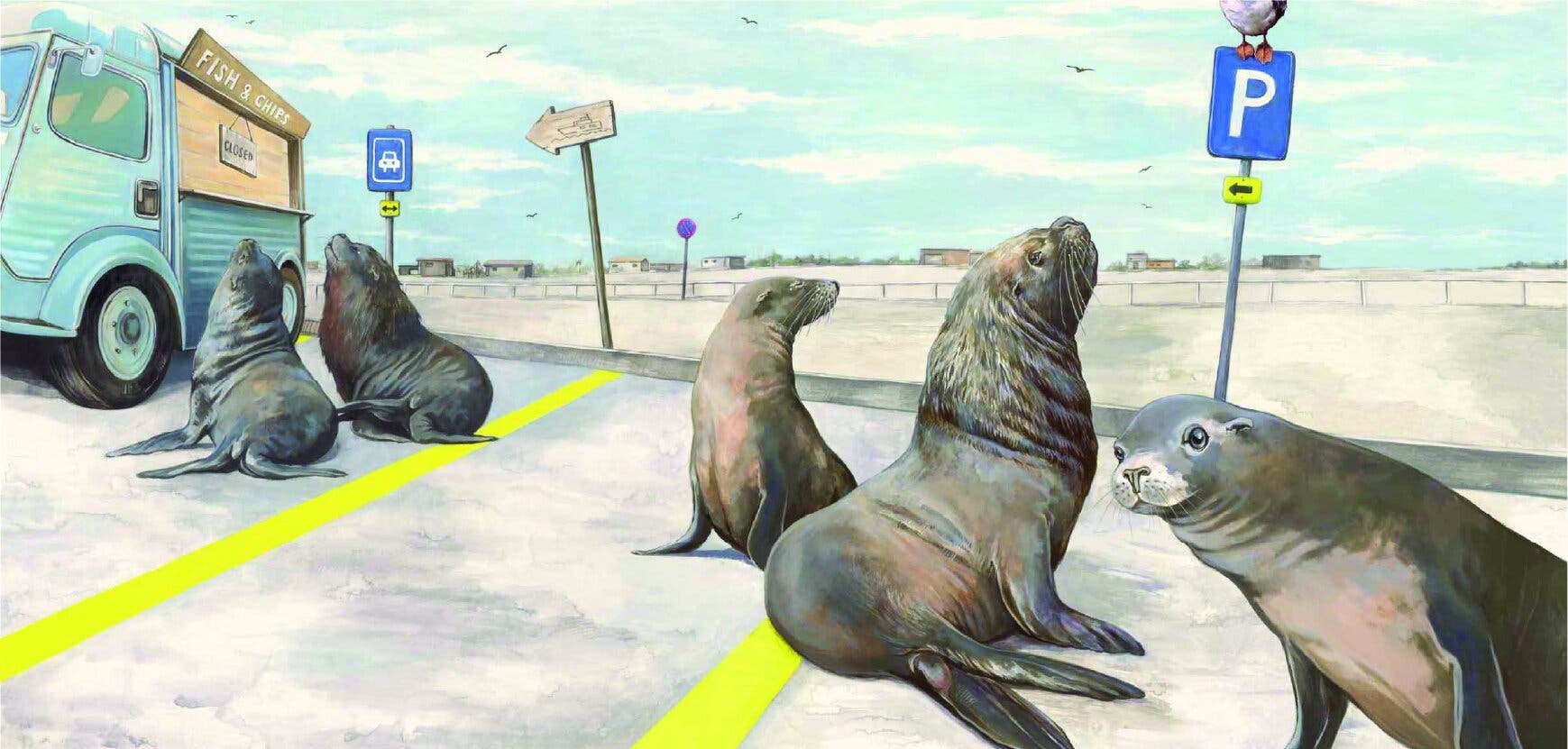

SEA LIONS IN THE PARKING LOT

Animals on the Move in a Time of Pandemic

Written by Lenora Todaro

Illustrated by Annika Siems

TRACKING TORTOISES

The Mission to Save a Galápagos Giant

By Kate Messner

Photographs by Jake Messner

It’s uplifting to see young people taking climate matters into their own hands and demanding action. But at the same time, they’re suffering from levels of eco-anxiety that are off the scale compared to anything I experienced at their age. Thankfully, writers and illustrators are responding to this new reality and making books that not only connect readers to animals and nature, as children’s books always have, but also help them understand what’s going on and reassure them that there are ways to defend our troubled planet.

“Sea Lions in the Parking Lot,” by Lenora Todaro and Annika Siems, tells the true stories of what 12 animal species got up to when Covid-19 kept people indoors. In years to come, these will surely be some of the few joyous tales told about the pandemic, during which so many of us were enchanted by animals moving into cities and we caught a glimpse of a world without humans.

This moment in time is gloriously brought to life on the page with brief descriptions and stunning, double-page illustrations of animals — playing, exploring and napping in peace — that will resonate with young readers.

There are Sika deer clopping up and down a subway escalator in Japan. In Kruger National Park in South Africa, a pride of lions warm their bellies in the midday sun, the biggest, happiest cats I’ve ever seen. Wild boar have a lovely time chewing flowers and splashing in the fountains of Haifa, Israel. There’s a soulful gorilla undisturbed by visitors in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda. And in Maine, frogs the size of paper clips are free to hop across roads without getting squashed flat.

An octopus in a Venice lagoon peeping out from under a discarded blue face mask hints at the darker side to these stories. In a well-balanced epilogue, Todaro explores more of what the “anthropause” has taught us about our complicated relationships with animals and the environment. Deserted beaches with the lights of resorts switched off were welcoming to nesting sea turtles, but without wildlife biologists watching over them more of their eggs were stolen by poachers. In Lopburi, Thailand, hungry macaque monkeys missing handouts from tourists were seen squabbling over what was believed to be an empty yogurt cup.

The book treads a careful line of pragmatic optimism, not shying away from the problems while showing how we can work toward a healthier world. It stands as an important reminder that things were different for a while, and guides readers toward deeper environmental thinking, about species and habitats and the interdependence of it all. The anthropause showed that wild animals can bounce back quickly given space and the right conditions to thrive.

Todaro offers readers suggestions of actions they can take — slow down, make more room for one another, volunteer and never feed wild animals — and keeps a firm eye on the bigger issues of overfishing, plastic pollution, habitat loss and carbon emissions. The selection of stories from all around the world subtly introduces readers to the idea of being global citizens. We are all in this together and it will take big, international efforts to achieve the radical changes needed to protect the environment.

Jake Messner

“Tracking Tortoises,” by Kate Messner, with photographs by Jake Messner (her son), transports older readers to the Galápagos Islands on the trail of giant tortoises. These enormous reptiles made the journey millions of years ago, floating 600 miles from South America (giant tortoises do float, scientists have verified), and evolved into at least 14 species.

There were no humans in the Galápagos until the late 1500s, when sailors, whalers and buccaneers arrived and began loading live tortoises onto their ships as a source of fresh meat during long journeys. By the late 1800s, as many as 200,000 tortoises had likely been killed in this way. Giant turtle soup is now off the menu, but fewer than 26,000 tortoises are left, and several species are extinct, including that of Lonesome George, who died in 2012. He was the last Pinta Island tortoise.

The Messners joined scientists in the Galápagos for a week in 2019, shadowing studies of the remaining giant tortoises and the modern-day threats they face. Central to the book is the puzzle of why tortoises bother hauling their 500-pound bodies up volcanoes each year. Tracking devices fixed to their shells reveal their ponderous treks.

We hear of Samuel, the tortoise who is still too young to migrate. So far he’s stayed within an area the size of a swimming pool. Maybe in another 12 to 15 years he’ll set off to feed on plants that grow in the fog-drenched uplands. Sebastian is older and bigger and normally migrates, but in 2011 he didn’t, probably because he got stuck behind a farmer’s fence. It takes years of long-term studies to learn the basic biology of these animals, and figure out what matters to them and how to help protect them.

For readers curious about what it’s like to be a scientist, the book provides superb insights via the stories of real people, on the page and in online video clips linked to QR codes. We meet the muddy-boots-on-the-ground field researcher Freddy Cabrera striding rocky trails and listening for the beeps of radio-tagged tortoises. Stephen Blake, the team’s leader, plugs a small infrared camera into the jack of his iPhone, transforming it into a thermal imaging device that takes tortoise temperatures. Sharon Deem and Ainoa Nieto Claudin, wildlife veterinarians, swab the mouths, eyes and tail openings of 200 tortoises and pass the samples to Irene Peña, a volunteer who prepares them for DNA testing to find out if these tortoises living in the wild are healthier than those living closer to civilization. Another researcher on the team, Diego Ellis Soto, analyzes a quarter of a million native plant seeds in tortoise dung (to see if the tortoises’ role as spreaders will continue to be positive) and calls it a “pleasure.”

This rich ecosystem of a book is about a lot more than tortoises. It’s about how science is done, by all sorts of people who put their minds together to answer important questions. And it opens doors to understanding the challenging times in which we live, the difficult choices we face and how we can go about building a more hopeful future.

Helen Scales, a marine biologist, is the author of six books. Her first children’s book, “The Great Barrier Reef,” will be published in 2022.

SEA LIONS IN THE PARKING LOT

Animals on the Move in a Time of Pandemic

Written by Lenora Todaro

Illustrated by Annika Siems

48 pp. Maria Russo/Minedition. $18.99.

(Ages 4 to 8)

TRACKING TORTOISES

The Mission to Save a Galápagos Giant

By Kate Messner

Photographs by Jake Messner

64 pp. Millbrook. $25.99.

(Ages 8 to 12)

Source : nytimes.com

Comment